When a historian sets out to tell the story of an event, they typically begin by looking at primary sources: newspapers, diaries, letters, photographs–any sort of item that records what happened from the perspective of those who lived it. Often these materials are stored in an archives, a repository that collects records and manuscripts of enduring value, like the Special Collections & Archives department at Coates Library.

But a historian is limited to the primary sources that survive to the present day. Someone at some point has to decide that each document is worth preserving. Sometimes this happens in a deliberate manner, sometimes it is by pure chance.

In his new book, West Side Rising: How San Antonio’s 1921 Flood Devastated a City and Sparked a Latino Environmental Justice Movement (Trinity University Press, 2021), former Trinity professor Dr. Char Miller describes how he came into possession of the US Army report on the devastating flood that provided the spark for his research:

Sometime in the late 1990s, while I was grading student papers in my light-flooded office at Trinity University in San Antonio, a man walked up to my open door, knocked on the metallic frame, and asked if we could talk…my visitor indicated that he worked as a civilian on Fort Sam Houston, saw that the report was going to be tossed out, salvaged it, and in time learned of my research. (Miller, 233-234).

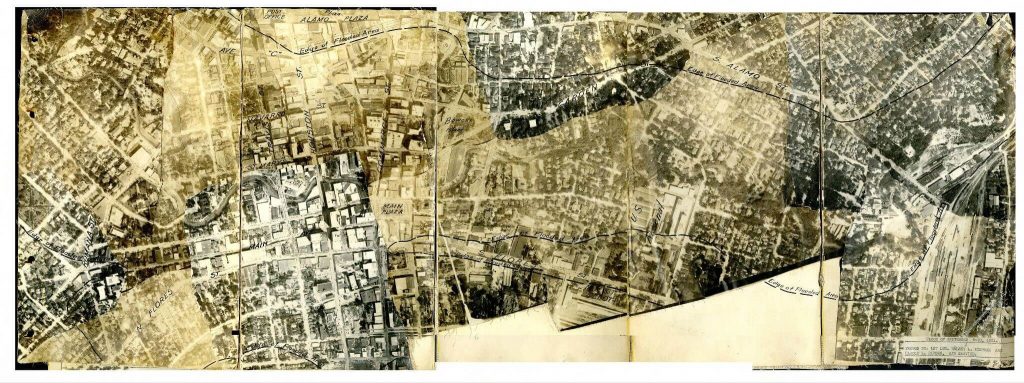

The report included pages of text, maps, photographs of the devastation left behind, and aerial photographs documenting the damage from military aircraft. It took a confluence of circumstances–someone with a preservationist instinct rescued the documents from the trash, then happened to find a historian interested in the subject, who then brought the documents with him as he moved across the country, and held on to them for twenty years until he finished his book–to bring these materials to their permanent home in Special Collections & Archives at Coates Library. Selected items from the report can be viewed on the library’s Digital Collections site.

Composite of aerial photographs of flood damage taken by the United States Army Corps of Engineers, including aerial views of Alamo Plaza, Houston Street, Flores Street, and the U.S. Arsenal. (Click on the image to be taken to the source.)

While these records were saved, it’s important to consider which accounts from the 1921 Flood were not. The US Army’s report was ultimately preserved, but did anyone save the diary entries of a teenage girl who was awoken by the flood waters? Or conduct oral histories with the Spanish-speaking residents of San Antonio’s West Side, who were hardest hit by the tragedy?

In his book, Dr. Miller draws upon eyewitness accounts in the San Antonio Express and La Prensa (the city’s Spanish language newspaper). While the entire archives of the Express-News is available online through the NewsBank database, only sporadic issues of La Prensa have been made available digitally to modern researchers. Unequal representation in archives of historically marginalized groups is a crucial issue that modern archivists and librarians are striving to address through reparative collecting policies and digitization efforts.

San Antonio’s West Side neighborhoods were devastated by the flooding of Alazán Creek on September 9, 1921, but future flood prevention efforts in San Antonio focused on protecting downtown businesses. (Click on the image to be taken to the source.)

Dr. Miller argues that the city’s response to the 1921 flood, which included the construction of the Olmos Dam just north of our campus, created persistent inequities between the wealthy, white neighborhoods of San Antonio and the poorer, largely Hispanic community on the city’s West Side. This systemic racism is not only visible in the city’s urban planning through the twentieth century, but also in how the histories of our city’s communities have been preserved by libraries and archives.

Just as the rising waters of Alazán Creek and the San Antonio River swept away homes and lives in September of 1921, the passage of time erases memories of events. Libraries and archives must work to preserve the documents that capture the true story of what happened, including voices from all communities, in order to enable the work of historians in the future.

Visit Coates Library Digital Collections to see photographs and maps of the 1921 San Antonio Flood. For more information about Dr. Miller’s book, visit the TU Press website.