The history of American medicine is also the history of Black contributions to American medicine.

Yet the stories of these healers, the details of their lives and innovations, are too often unknown or overlooked. To commemorate this year’s Black History Month, the theme of which is Black Health and Wellness, I’ve showcased three remarkable medical practitioners. In writing these profiles, I relied on information found in library databases such as the African-American Experience and the African-American Studies Center.

Rebecca Lee Crumpler, 1831 — 1895

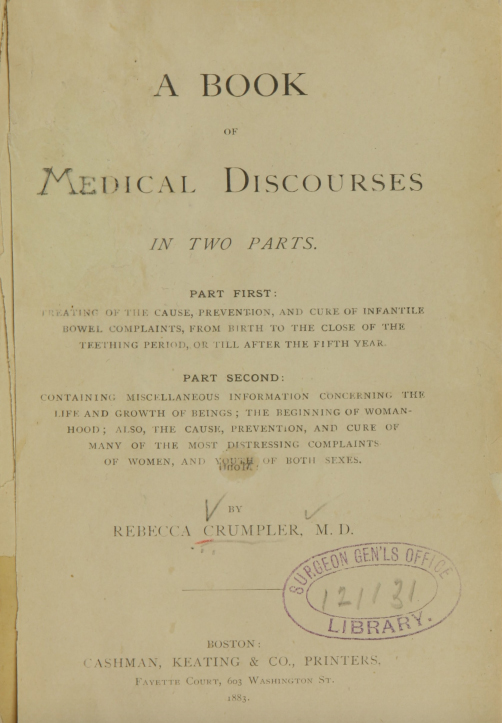

Crumpler was the first Black woman to be formally trained as a physician. Inspired by her aunt, a sought-after folk healer, Crumpler worked as a nurse in the Boston area before being admitted to the New England Female Medical College (now part of Boston University) in 1860. “I early conceived a liking for, and sought every opportunity to be in a position to relieve the sufferings of others,” Crumpler would later write. After four years of arduous study, Crumpler became the 48th graduate of the school, earning the title “doctress of medicine.”

After the Civil War she practiced medicine for the Freedmen’s Bureau in Richmond, Virginia, where she treated many former slaves and poor people who lacked access to quality healthcare. She was especially concerned with the health of women and children, and persisted in treating them despite discrimination from White peers. According to a 1964 Ebony article about Crumpler, “men doctors snubbed her, druggists balked at filling her prescriptions, and some people wisecracked that the MD behind her name stood for nothing more than ‘Mule Driver’”.

By 1869, Dr. Crumpler had returned to Boston, where she married, had a daughter, Lizzie Sinclair Crumpler, and continued practicing medicine. In 1883, she published A Book of Medical Discourses, in which she recorded all that she had learned from a lifetime of treating women and children. She dedicated the book to “Mothers, nurses, and all who may desire to mitigate the afflictions of the human race.” On March 9, 1895, Crumpler died at the age of 64. No photographs of her survive, but she was described in an 1894 issue of the Boston Daily Globe as “a very pleasant and intellectual woman … tall and straight, with light brown skin and gray hair”. Read more about Dr. Crumpler in this biography by Sarah K. Pfatteicher, or this 2021 obituary published by the New York Times.

Charles Richard Drew, 1904 — 1950

Charles Drew with his wife Lenore and their three daughters at the piano

“Charlie” Drew was a surgeon and physiologist who today is remembered as the father of blood banking. Drew studied at McGill University Medical School where he graduated second in his class. After completing his residency in Montreal, Drew taught at Howard University as instructor of pathology, and at Freedman’s Hospital as assistant instructor in surgery.

In 1938, he was awarded a two-year fellowship at Columbia University, where he studied blood storage for his doctoral dissertation. Drew demonstrated that blood donations could be kept longer if red blood cells were separated from plasma, preventing hemolysis, or disintegration of red blood cells. This separation promoted further research into the uses of plasmapheresis, a “therapeutic intervention that involves extracorporeal removal, return, or exchange of blood plasma or components”. Today, this procedure is used to treat numerous diseases. Dr. Drew’s expertise in blood products was especially critical during World War II. He helped organize the Blood for Britain program, an experience that motivated his postwar research into refrigerated bloodmobiles.

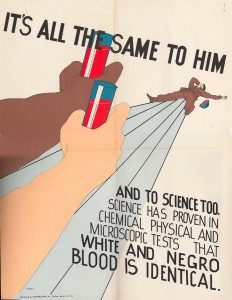

In 1941, Dr. Drew was named the first director of the American Red Cross Blood Bank, an influential post from which he denounced the practice, then employed by the Army and Navy, of segregating blood by race. “I think the Army made a grievous mistake,” Drew wrote in a 1944 letter to the director of the Labor Standards Association. “A stupid error in first issuing an order to the effect that blood for the Army should not be received from Negroes. It was a bad mistake for 3 reasons: (1) No official department of the Federal Government should willfully humiliate its citizens; (2) There is no scientific basis for the order; and (3) They need the blood.”

A leaflet protesting the Red Cross’s policy of blood segregation, distributed by the Congress of Racial Equality

Dr. Drew’s life was cut tragically short by an automobile accident in 1950. He was just 45 years old. But his legacy lives on: at the historically black medical school named in his honor, and in the millions of lives saved each year by blood donation.

Read more about Charles Drew in the African American Experience, or in this summary of his accomplishments, published by the National WWII Museum.

Mae Jemison, 1956 –

Mae Jemison floating in zero G aboard the space shuttle Endeavour

Jemison may be best known as an astronaut––she was the first woman of color to be selected for a NASA space mission. But she was made eligible for that honor by a sterling career in science and medicine. At just 16 years of age, Jemison matriculated at Stanford University, where she would eventually graduate with a degree in chemical engineering. Afterward, she attended Cornell University Medical College (now Weill Cornell Medicine), where she earned her MD. During graduate school, she studied in Kenya and Cuba, and treated Cambodians living in a Thai refugee camp. These experiences impressed Jemison deeply, inspiring her to join the Peace Corps as a medical officer for Sierra Leone and Liberia. During this time she also worked with the Centers for Disease Control, contributing research toward the development of a hepatitis B vaccine.

After her stint in the Peace Corps, Jemison moved to Los Angeles where she worked as a general practitioner––but not for long. In 1987 she was chosen out of roughly 2,000 applicants to join NASA’s astronaut corps. Five years later, on September 12, 1992, Jemison joined six other crew members in traveling to space aboard the shuttle Endeavour. As science mission specialist, Jemison co-investigated a bone cell research experiment. She was also responsible for testing NASA’s Fluid Therapy System, a technology for producing saline solution in space.

After leaving NASA, Jemison founded a technology consulting firm, The Jemison Group, and later taught environmental studies at Dartmouth College from 1995 to 2002. She is also the author of a memoir, Find Where the Wind Goes, and four books for children about the solar system.

* * *

These are just three of the many pioneers who worked to advance the frontiers of Black health and wellness. The knowledge they created is now the common heritage of all humankind. But we shouldn’t take too narrow a view of innovation, or overvalue the contributions of certain individuals, however heroic their work. As the Association for the Study of African American Life and History reminds us, advances in medicine come not only from doctors, clinicians, and nurses, but also from “birthworkers, doulas, midwives, naturopaths, [and] herbalists throughout the African Diaspora”.

Want to learn more about these remarkable people? Read this research guide curated by Beverly Murphy, a medical librarian at Duke University, and herself a Black woman. And of course you can (and should!) explore the wide array of African-American resources at Coates Library.