This post was written by Lindsey Bonin ’22, the Exhibits Intern in Special Collections & Archives for Spring 2022.

When you first walk into the Special Collections & Archives reading room, you’d be hard-pressed to miss the ten-foot-tall woven tapestry that takes center stage in the room. Elizabeth Huth Coates Maddux, the library’s namesake, designed the Rare Book Room specifically with this tapestry in mind and it was finally bequeathed to the library upon her death in 1996. It depicts an allegorical representation of America as a goddess holding an arrow and quiver, surrounded by exotic fauna, including a crocodile winding around her legs. Until now, the Maddux tapestry has lacked historical context and recognition of the indigenous peoples who are both represented and erased in its depiction of North America. The new exhibit case in the reading room seeks to address this lapse by exploring how indigenous Americans were represented by others and how they represented themselves.

Created in the late 17th century, the Maddux tapestry was designed by Lodewijk van Schoor, a Flemish artist who likely had never stepped foot in the Americas. The weaving industry in Brussels during this period was considered the best in the world and tapestries from that historical moment are highly valued by museums and private collections today. The Maddux tapestry was created as part of a series titled “The Four Continents,” which personified Africa, America, Asia, and Europe as classically styled goddesses surrounded by identifying landmarks and natural components. Many post-Colombian European artists employed the Four Continents motif as an expression of dominion and colonial imagination of indigenous people.

“America” tapestry designed by Lodewijk van Schoor, woven by an unknown weaver in Brussels.

Material objects teach us about the past and art especially can inform us about how worldviews of the past were depicted and distributed. Art is always a part of political discourse, and the Four Continents device served to advance the politics of white supremacy. The Maddux tapestry, for example, employs the “Indian princess” stereotype which privileges European features and emphasizes the “otherness” of Native Americans. The tapestry also prominently features a European ship entering behind the figures, centering European colonists in the artistic representation of the American continent.

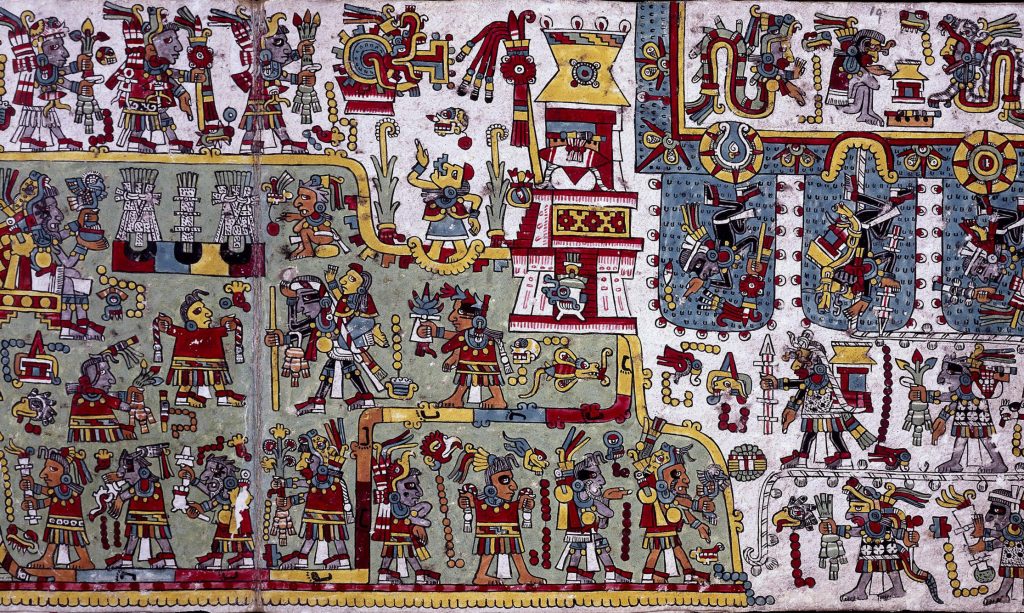

The Maddux tapestry can inform us about how Europeans of the 17th century imagined the people of America, but how did these indigenous Americans imagine themselves? Two facsimiles now displayed in front of the tapestry can help us begin to answer this question. The Codices Tonindeyé and Yohualli Ehécatl are pre-contact manuscripts from the Mixtec civilization in what is now southern Mexico. They contain diverse subjects, from religious calendars to divination instructions to royal biographies. In records like these, indigenous people represented their own history and values. Native Americans self-represent in diverse ways across the continent, but these Mixtec codices offer a unique artistic interpretation of the self completely uninformed by European colonization. In an effort to further center the indigenous creators of these works, the Special Collections staff has chosen to present them under indigenous-language titles rather than the common titles named for white collectors.

Page from the Codex Tonindeyé from the Teozacualco kingdom, around 14th/15th centuries C.E. Image courtesy of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Although the Maddux tapestry carries great aesthetic value for the Special Collections reading room and historical value as a piece of art, to privilege artistic value over historical context would be to silently endorse the colonial worldview it represents. The new exhibit provides context for the motivations behind such a characterization and offers an alternative means for self-representation by indigenous subjects.