Welcome back Trinity community!

As you walk through Starbucks you’ll notice three new posters highlighting some of the great research our Trinity faculty and students have published recently.

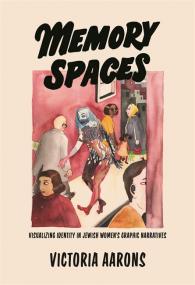

Librarian Anne Graf had an opportunity to ask Dr. Victoria Aarons, O.R. & Eva Mitchell Distinguished Professor of Literature, about her new book Memory Spaces: Visualizing Identity in Jewish Women’s Graphic Narratives.

Here is what they discussed:

What drew you to the work that would become your new book, Memory Spaces: Visualizing Identity in Jewish Women’s Graphic Narratives?

This book is, in many ways, an extension and outgrowth of my previous book, Holocaust Graphic Narratives: Generation, Trauma, and Memory. I am interested in the ways in which memory—individual and collective or cultural memory—fashions identity. My area is, primarily, Holocaust Studies, a field that overlaps, in richly fluid ways, with Jewish Studies as well as Memory and Trauma Studies. I am particularly interested in forms of representation, especially contemporary expressions that combine genres and disciplines. The graphic novel, as genre, is a hybrid medium that, in the juxtapositions and intersections of text and image, materializes subjectivity and foregrounds the performance of identity as it is played out over time. The medium allows comics artists to visualize both time and space and thus fill the absences created by loss by drawing memory on the page.

I came to do work on the graphic novel—a medium that was new to me—as a result of a class I was teaching on literature of the Holocaust. As is so often the case at Trinity, our students pulled me in a new direction for research. At the end of the semester, several students approached me and asked if I would consider teaching a class on the graphic novel. I had included a graphic novel, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, in the class, and my students were particularly drawn to the genre as a felt expression of the transmission of intergenerational trauma and memory. Maus was really the only graphic novel with which I was familiar, and my initial inclination was to say “no.” However, the more I thought about it and the more research I did, the more excited I became about teaching a course on graphic novels, and specifically on Jewish graphic novels. The first class was a success largely because of my students, who no doubt knew more about the conventions of comics than did I. The course resulted in the first book, which, then opened itself up to my current publication Memory Spaces.

How did you select the narratives analyzed in the book?

I wanted to focus specifically on Jewish women comics artists, and I selected those texts that reflect a range of approaches and artistic styles. The graphic artists I examine invent worlds on the pages of their work in an attempt to reclaim agency and stability. Memory in these works functions rhetorically as a trope of recovery and reckoning, providing a context for self-construction and identity formation, a stabilizing structure and framework within which one might reconstitute the fractured or traumatized self. These are deeply confessional works that expose intimate and urgent landscapes and that reckon with defining moments of trauma. The characters and narrating personae in the graphic narratives I am most interested in, persistently grapple with a sense of fragmented or fractured identities. They are staged in visual encounters with themselves and with real or imagined histories and narratives of the past. And memory is the screen through which the narrating mercurial self is viewed, shaped, and reclaimed. I also selected those autobiographical or semi-autobiographical texts in which the graphic artists draw themselves through their graphic avatars as other in their attempts to expose the subjective expression of self.

Is there anything you discovered or realized in the course of your research that surprised you?

I continue to be amazed by the variety of ways in which graphic artists manipulate time and space on the page. Memory itself is polyphonic; voices, impressions, and sounds from the past intermingle with and adjudicate the present. We are in two conceptual and temporal spaces simultaneously. I also continue to be surprised and delighted by the number of new graphic narratives—visual forms of storytelling—that have been and continue to be published by young, emerging artists. The graphic novel is a medium of our times.

Did your research experience raise any additional questions for you regarding this field of study?

All good research leaves you with more questions than you started with. I’m thus currently working on an edited collection, tentatively titled Drawing Memory, in which I’m focusing on the function of silence in graphic narratives. I’m interested in the following questions: How do silent panels constitute moments of reflection that slow or halt the movement of the unfolding narrative? How do visual moments of silence pull the reader into the panel, inviting the reader to engage in a mutually constitutive process of interpretation along with the comics artist? How does silence evoke moments of traumatic rupture?

Thank you Dr. Aarons for taking the opportunity to share with your Trinity community.

We are excited to be able to highlight faculty research in the library. Dr. Aarons’ new book is available for checkout.

The library also has a collection of graphic novels both in ebook format and in print.

Graphic novels are shelved based on their topics and can be found via the library catalog.

For research about graphic novels, make your way to the fourth floor to the PN 6700 section, or you can browse the library catalog for “graphic novels” to see a variety of titles and formats.

As always, the library service desk can help you locate any materials.