Librarians. Stereotypically quiet and introverted, bespectacled and mousy, they perform an admirable and important job, but let’s be honest, they’re pretty boring, right? Well, like people in any profession, they can be. Until extraordinary circumstances call for them to execute the highest duties of their vocation, that is. Below are some examples of “hero librarians” who were so committed to protecting the light of knowledge that they literally risked life and limb.

Abdel Kader Haidara and the Badass Librarians of Timbuktu

In 2012, a terrorist faction known as Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) seized control of Timbuktu, the ancient capital of Mali, in western Saharan Africa. Reports began to emerge that the AQIM occupiers were conducting “search and seize” raids in houses and businesses in the Malian capital of Bamako in an effort to suppress non-Wahhabist thought and religious practice. Growing increasingly alarmed, a man named Abdel Kader Haidara, the librarian of Timbuktu, hatched a plan to protect the thousands of priceless documents and artifacts from that library.

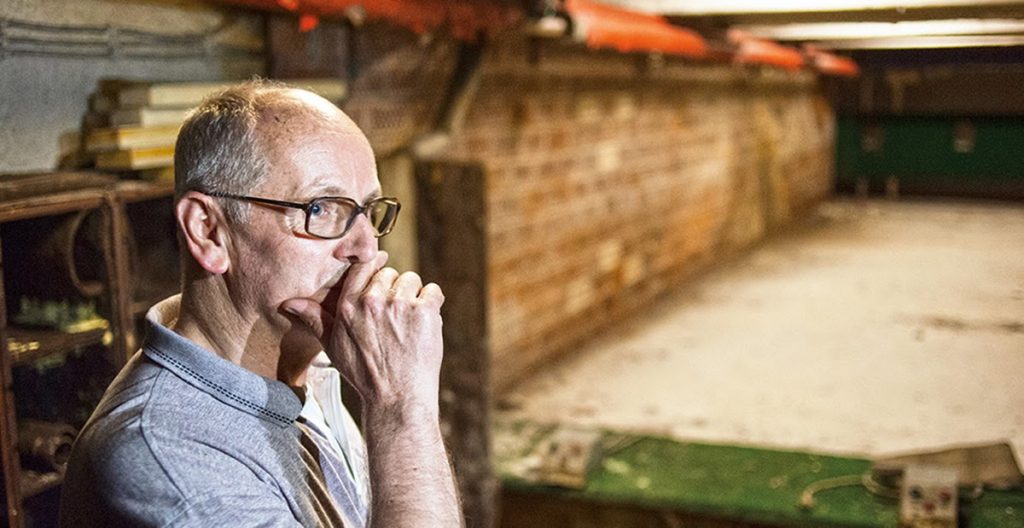

Abdel Kader Haidara in 2009. [“Manuscripts from the Mamma Haidara Library, Timbuktu” by The Robert Goldwater Library, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license. Via flickr.com]

Mustafa Jahić and the Librarians of Sarajevo

With the collapse of communist Yugoslavia in 1992, war broke out across the newly established nation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Snipers lay in wait around seemingly every corner of the capital Sarajevo, and by the end of the three-year conflict, more than 5,000 civilians had been killed throughout the city and two major libraries had been ransacked by the Serb militia. But librarian Mustafa Jahić and a handful of brave colleagues refused to let the 470 year old Gazi Husrev-beg Library suffer the same fate.

Mustafa Jahić [© 2016, Boryana Katsarova. Aramco World, https://www.aramcoworld.com/Articles/January-2016/Saving-Sarajevo-s-Literary-Legacy.]

The US Library War Service

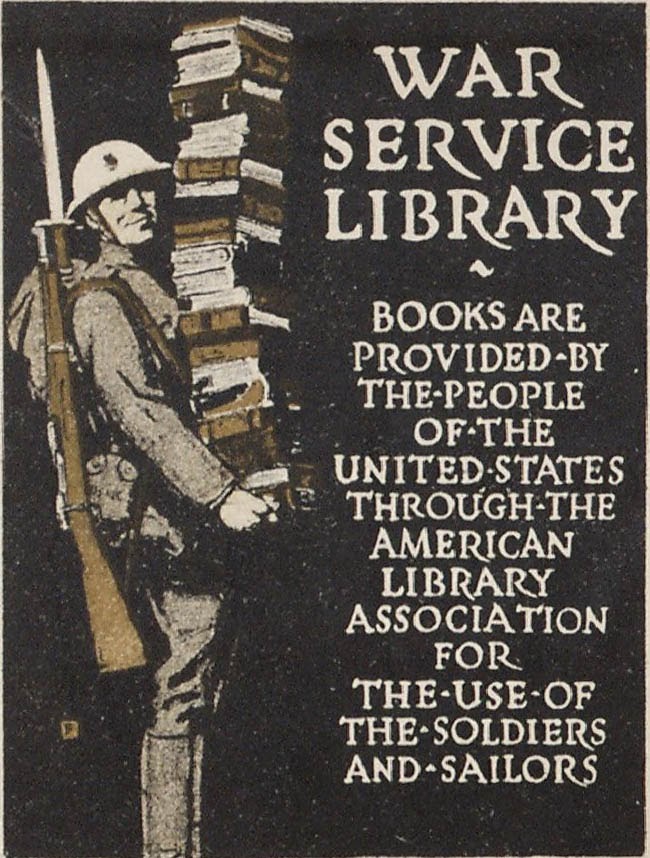

“War Service Library” sign, 1918. [American Library Association. Public domain.]

Perhaps the lesson to be gleaned from these accounts is not that librarians are any braver than other human beings, but that they often believe in their vocation with as much commitment as anyone ever has.

Recent Comments