“The most precious treasure is never fully known.”

-Song Dynasty poet Yang Wanli (1127 – 1206), “Bubbles On the Water”

I certainly think this could be said about library collections. On our first floor in the mobile shelving units we hold a small but significant set of works on East Asian topics and/or written in East Asian languages. It’s an unsung treasure of Coates Library.

On the lighter side, fans of K-pop, for example, who want to understand what BTS are actually singing about, or K-drama fans who want to have a better grasp of the dialogue in all those great Netflix series might want to check out A Korean-English Dictionary, by Martin, Lee, and Chang. (A Basic Glossary of Korean Studies might help, too!) Trinity students whose first language is Spanish but who want to learn Chinese could make good use of the Diccionario Español-Chino. And if you’re planning a trip to a Mandarin-speaking country you might consider borrowing the Chinese/English Phrase Book by John Montanaro. (You don’t have to be able to read Chinese characters to use it — it’s all in Romanized transliteration!)

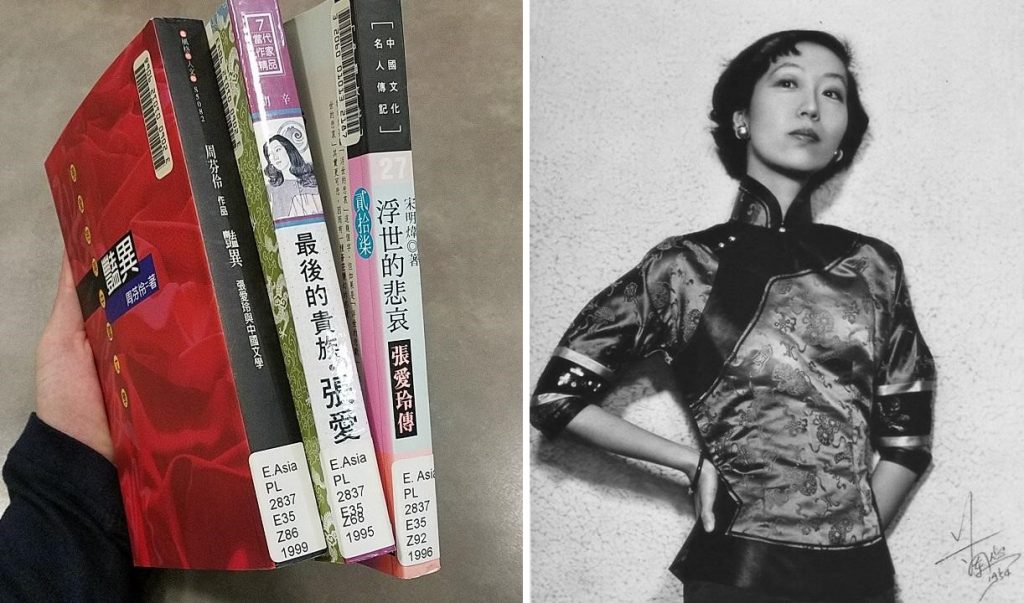

If you do read Chinese, you might be interested in the biographies and literary criticism titles we have on Chinese-American writer Zhang Ailing (aka Eileen Chang), one of the leading figures in 20th century Chinese feminist literature.

(L) Our biographies of Eileen Chang. (R) Eileen Chang in Hong Kong, 1954. public domain.

The crown jewel of the East Asian collection, however, is the 600-volume Sì Bù Bèi Yào (loosely, Four-Category Library of Essential Writings), call number AC149 .S8 1964.

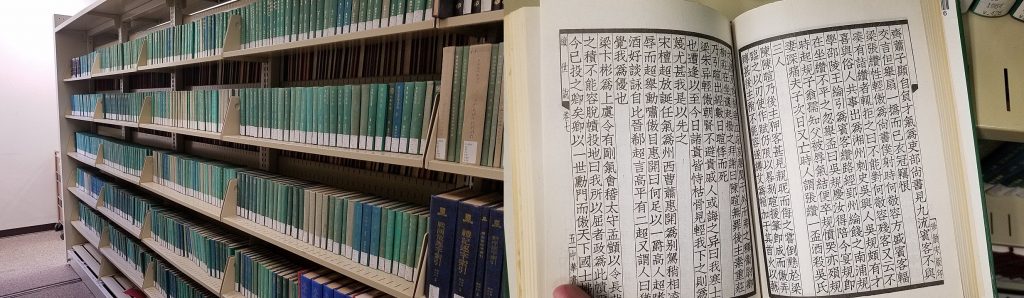

The library’s East Asian collection, located on the first floor.

This is a collection of the most important writings and commentaries from all periods of Chinese history up to the early 20th century, and is divided into the four traditional categories (sì bù)* of the Chinese library, covering Confucian Classics, Philosophy, Historiography, and Belles-letres. Our copy of the collection, held by only 12 other libraries in the United States, is a 1964 facsimile reprint of the now rare 1936 edition compiled by the Zhongua Publishing House in Beijing. The Sì Bù Bèi Yào is written in Literary Chinese, which is read from top to bottom, right to left, and which was largely replaced by Written Vernacular Chinese during the 1920s in most of the Sinophone world. (Written Vernacular Chinese follows a left-to-right horizontal format similar to that of Western languages.)

* “This [four-category] system is quite probably derived from a physical arrangement in the four storerooms of the imperial library during the Jin period (265-420).” [1]

Because it holds thousands of years of Chinese history and literature spread across tens of thousands of pages, to adequately summarize the full contents of the Sì Bù Bèi Yào would be impossible. But it’s worth remarking on some of the key works within therein:

One of the more fascinating items found in the Sì Bù Bèi Yào is a text transcription of Shénnóng’s Book of Materia Medica (Shén Nóng Běncǎo Jīng), a compendium of useful plants, pharmaceutical preparations, and treatments of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Public domain. Source: china.org.cn/top10

The Shén Nóng Běncǎo Jīng is believed to have been compiled during the Han Period (206 BCE – 220 CE) and attributed to the mythical emperor Shén Nóng [2], who is often portrayed with an ox head or simply with bovine horns, as seen in this woodcut.

“Chinese Woodcut; Famous Medical Figures: Shen Nong”, Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 4.0 International: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en

Of further Traditional Chinese Medical interest is Zhang Zhongzhing’s (150 – 209 CE) beautifully named treatise Jade Letters from the Golden Chamber (or perhaps more accurately, Essential Prescriptions from the Golden Cabinet — either sounds more elegant than Physicians’ Desk Reference!).

There is a vast amount of beautiful poetry within the Sì Bù Bèi Yào, in particular from the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279):

I am a butterfly journeying to the eight corners

of the universe.

Outside the boat, waves crash like thunder,

but it is silent in the world of sleep.

-Yang Wanli, (1127 – 1206)

Other notable Song poetry found in the Sì Bù Bèi Yào are the works of Su Shi, Lu You, Lin Bu, and the great female poet and essayist Li Qingzhao (1084 – 1155).

“Li Quingzhao Statue” by Gisling, via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 3.0 Unported: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

We find also in the Sì Bù Bèi Yào the Qing period (1644-1911) commentaries to the Thirteen Confucian Classics, a collection of texts reflecting the teachings of Confucius, whether or not actually penned by him. The Thirteen Classics were compiled during the Han Period (206 BCE – 220 CE) and their philosophical and stylistic content later came to form the basis of the Song Dynasty’s civil service examination system and consequently heavily influenced East Asian thought. [3]

We hope this brief overview of our East Asian holdings whets your appetite to know more. But perhaps we can rest content in the notion that, as Yang Wanli tells us, “the most precious treasure is never fully known.”

[1] http://www.chinaknowledge.de/Literature/Terms/sibu.html

[2] http://www.chinaknowledge.de/Literature/Science/shennongbencaojing.html

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thirteen_Classics

Recent Comments